Cradock is an unexceptional town. It was founded around 1818 and has served, for the most part, as a stopping off point for people going to other places ever since. It’s a small town, and like many small towns, has come to invest not inconsiderable effort in trying to write for itself histories of various kinds. Tales of local boys and girls who made good. Characters and places given special focus as being quite unlike any other. The town has an information office, two actually. The older and uglier is downplayed though, in favour of the extensive signage of the new municipal desk, featuring the ubiquitous white ‘I’ that is so excellent at capturing passing tourists.

Inside the information office, on a regular day, visitors can expect to encounter every colour and shape of paper plumage growing from the pamphlet stands. Spas featuring warm, rejuvenating sulphur baths, converted old Karoo houses that you can stay in, and drives and tours and adventures of every conceivable kind. An accredited tourguide, resplendent in his multi-pocketed jacket and polished accreditation badge, will take you to see the historical buildings in town, the Zebra in the nearby national park, or fauna of a different variety in the nearby township. Poverty is a terrible thing, but the shacks make for such gorgeous photographs, darling.

Also inside the aforementioned information office, on the aforementioned regular day, you could expect to meet Nomthandazo Krawe – the information office’s information officer. “People like to create stories about everything.” she would say, handing over an accommodation directory book as thick as your thumb (it’s free, take one). Stay a little longer, ask a few more questions and Nomthandazo might tell you a few. There was the former principal of Goniwe High School, whose car was suddenly set on fire one afternoon. She’s quite sure that it probably had something to do with being a white teacher in a township school, but the residents who saw it happen insisted the car burst into flames because of the sun on a particularly hot day. She grins.

Those are the less-well known stories. The well-known ones are far easier to come by, and Nomthandazo will happily trot them off to the curious visitor with a well-rehearsed polish. The town is famous for being the home of Olive Schreiner, a long-dead author of The Story of an African Farm. A radical liberal and very early feminist, though less complimentary accounts of her life would salaciously frame her as being perhaps a little unhinged. But she was famous, you realise? Then there are the windmills. Made from scrap metal, wire, aerosol cans and other bits and pieces, they are works of art particular to Cradock. You can buy them direct on the side of the road as you enter the town. There by the giant yellow sign proclaiming ‘Karoo Art’. If you miss the sign, you can always carry on into town and buy them at twice the price in a ‘proper’ store, such as unfortunately named ‘Shop Karoo Shop’ (if you read the sign in a particularly cheeky state of mind)

The more critical of the tourguided might reflect on the implications of some of those under the umbrella getting to carve their logos into the graves for posterity

Cradock’s most famous claim to fame, however, lies in its anti-Apartheid struggle credentials. The Cradock Four of Matthew Goniwe, Sparrow Mkhonto, Fort Calata and Sicelo Mhlauli may not have been Cradock’s golden children during their lives, but in their deaths left a precious legacy that has been mined by Cradock’s nascent tourism industry for decades. The graves have been refurbished, with the logos of South Africa’s tripartheid alliance partners nicely carved into the marble as the UDF (United Democratic Front) logo peels from the stone in the parts of the site that were presumably not paid for by the ruling party. That the ruling triumvirate of modern South Africa was banned at the time of their deaths is a minor factual detail. And that Goniwe et al were actually, officially, representatives of the UDF is not something that visitors to the site should really dwell on as they look on from outside the graves’ metal enclosure – presumably put there to keep the more boisterous representatives of the people from stomping on an important piece of history.

“We were all [African National Congress] members… in camouflage” clarifies Amos Nteta, a Cradock local and tourguide resplendent in pocketed jacket and official badge, “We were ANC, SACP, whatever, underneath the umbrella of the UDF”. The more critical of the tourguided might reflect on the implications of some of those under the umbrella getting to carve their logos into the graves for posterity while the umbrella itself will be little more than a memory in a few more decades. The more critical might. Most will happily snap a token photo with The Four and move along the tour.

Mounting the Tourism Pony

Amos has been in Cradock a long time. Born here, he is optimistic about the town’s future potential. “Cradock is picking up from tourism” he enthuses as he shows visitors around Cradock’s newly constructed cultural village and tourism center, which sits a few kilometers out of town. It lies beneath the watchful gaze of the Cradock Four Garden of Remembrance on the hill above. which is apparently beautiful, but wholly inaccessible unless you are the owner of a 4×4 or prepared to walk the kilometer or so up the hill to see it. Like the Cultural Center, it appears to be a masterful expression of enthusiasm by the Cradock municipality towards ‘developing’ the town’s cultural and historical assets. Only the absence of an actual road to the gardens and current lack of visitors to the cultural center hint that there remains some work to be done before the town can make the most of arriving tourists.

Infrastructurally, the cultural center is something to remark on. Flat screen televisions and fully kitted conference facilities are standard and the cultural center’s own tourguide and current caretaker, Lukhanyo Gxowa, proudly shows off chalet after chalet packed with enough mod cons to make them an attractive sell to anyone looking for accommodation or conferencing in the town. At R180 a head for a night there, they are also less than half the rate of the more established operations in the Cradock town center. It’s a steal, and it’s open, so why – as Kevin Costner would put it – if you have built it, has no one come?

If you look at the people who benefit from this town, it still benefits white people

It’s not from a lack of visitors – Gxowa stresses that there have been “more than last year, especially after the 2010 World Cup.” He explains that the cultural center is hoping to market itself with the cooperation of some of the more longstanding accommodation establishments in town, but that it’s early days and they have yet to show results for their efforts. Cradock town councillor Mlulani Henge shares this expectation for tourism, and initiatives like the cultural center, to help develop the town. “If you look at the economic potential of this area; besides agriculture, tourism is one area with a potential to grow this town”, he explains. He is slightly more blunt in explaining any lack of cooperation between the town’s established tourism businesses and the municipality’s recently competing enterprises, “If you look at the people who benefit from this town, it still benefits white people”

Superficially, it’s not hard to find white people in Cradock who sit fairly high up the town’s economic pyramid, far removed from the structure’s large – and largely black – base in the township around the municipality’s fledgling cultural center. The owner of the particularly successful Tuishuise bed and breakfast-cum-hotel has, over the years, purchased the entire street of houses on which the hotel resides in which to create a karoo-chic utopia, home by home. The houses were a steal, as the original residents ran into hard times and sold cheap. Their poverty also meant that the burgeoning hotel purchased the houses largely unmolested, since the original owners lacked any funds to modernise them. The result of this expansion is a road of beautifully-painted, old-Karoo style houses, complete with aloes in the gardens and shopfuls of authentic antiques in the expansive interior rooms. It is, in the words of its website, “a grand old colonial hotel that welcomes you with hearty country fare and décor from the days of Cecil John Rhodes, Olive Schreiner and the droves of adventurers who passed here en route to the hinterland.”

Prepare to be Storyed

The hinterland of the present Cradock, as much as it did in the past, still titillates would be Karoo adventurers with its stories of strange and wild people in villages (cultural or otherwise). It’s a source of valuable material from which many stories, as Nomthandazo would reflect from the information office, can be created. And the stories of the Karoo hinterland are being thoroughly told. The style of ‘Karoo story’ – an idiosyncratic blend of human interest, natural beauty and the romantic thrill of the explorer in the place few go to – is an extensively developed part of South African literary and photographic canon. From the pen of authors such as Dana Snyman to the photographic eye of Obie Oberholzer and the commercial imaginings of a decade or more of South African travel magazines, Karoo mythology is a large and polished beast.

Most recently, Cradock became the base of operations for Chris Marais and Julienne du Toit, award winning travel writers and photographers with a particular fascination for the Karoo story. Their most recent book, Karoo Keepsakes, is on sale in guest houses and tourist stops across the country. And on the shelf of Shop Karoo Shop, a short walk from the Tuishuise, if you need a copy during your stay in Cradock. Its glossy pages recount fabulous stories of the weird and wonderful things to be found in the surrounding areas, and have contributed to further establishing an idea of the Karoo as an iconic brand in the South African traveler’s mind. For those feeling intrepid enough to explore the hinterland – and what better place to do so than from a home base at Cradock – there are a litany of esoteric places to rediscover.

There is the world’s second-largest windmill museum. There are astronomical observatories out in the middle of nowhere, like scientific gems watching the clear Karoo skies. There are nomadic goat herders who have been herding goats nomadically for generations, and there are the ‘karretjiesmense’ (cart people) who have been traveling from Karoo farm to Karoo farm in their donkey drawn carts for a very, very long time. All stories to be explored, rediscovered for yourself in the Karoo, and an asset to the aspirations of towns such as Cradock to development-through-tourism. Particularly if you own a street full of “beautifully-painted, old-Karoo style houses, complete with aloes in the gardens and shopfuls of authentic antiques in the expansive interior rooms”

It’s an unfortunate inconvenience that not all of the fictional foundations of the Karoo story are as warmly embracing as copies of Karoo Keepsakes in Shop Karoo Shop or the colourful brochures of the Cradock information office would exuberantly assert. Some twenty or so kilometers out of Cradock, a suitably attentive adventurer can find the karretjiesmense for themselves. Having long since sold their karretjies, they now camp, four to a tent, on the side of a farm driveway. Helena Bramwell, 71, will gladly tell you the story of the group if you will be so kind as to purchase alcohol. That they are now committed to permanently settling on the side of this driveway in the biting wind, making the most of odd jobs here and there to get enough money together to subsist. She will tell you a dozen different ways that days are hard and unromantic. A dog tethered to a tree in their encampment, a week or two from death, will tell you silently with its cataracted eye and protruding bones that the days are hungry too. Helena will not tell you that she drinks to much on weekends, and that the kids sometimes go unfed. That there are three orphans in the party because their dad was bludgeoned to death in an argument with a man in another tent and their mom walked drunk in front of a train.

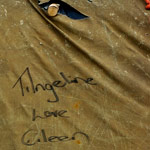

Helena Bramwell, 71. When her daughter asked for mielie meal, she wanted beer. And was put out when Thomas returned bearing only food.

The Cradock municipality has tried to help. “It’s not even a shack, the places these people are using as a shelter” says councillor Gxowa, who seems genuinely pained as he explains that they have tried to offer the karretjiesmense government housing in the past, but that they have consistently refused to move from their torturous roadside camp. “Their jobs come from the farms” he explains, and adds that their children are attending a farm school nearby and are afraid that if they take the risk and moving doesn’t work out, “they may see the school closed” and be trapped.

As we were leaving, I finally managed to get close enough to him to scratch his head. He will probably not survive until the end of the month without rescue. I've heard nothing back from the SPCA.

Change Wears the Face of a Sugar Beet

Jobs are something that Cradock municipality is taking seriously. The town is on the cusp of building an ethanol refinery, fed with sugar beetroot from thirteen farms that the Department of Land Affairs has purchased in a program intended to create jobs for people in Cradock in agriculture, transport and processing. “It is a project that has been coming for some time” says the councillor, “It was well-received – people had been waiting for this for a long time.” Yet while the construction and operation of the refinery holds the coveted promise of employment for many of Cradock’s poorest citizens, some residents, including the authors of Karoo Keepsakes, resist its development. Chris Marais cites environmental concerns, mixed with apprehension as to the effect of a nearby refinery on the character of Cradock as a tourist destination.

This story seems to already be written though, in a town where many have come to feel that the economic order cannot persist. “You can’t run away from the fact that people are still getting exploited.” explains Nomthandazo at the information office. And so change comes to Cradock, wearing the face of a sugar beet ethanol plant. Challenging its established order and the stories it has come to tell about itself, it remains only to be seen, once the much-described Karoo dust settles, how much will be changed. As councillor Gxowa sums it up, “It is one thing to see that the thing is well-supported. It’s another to see who will benefit from it.”