There was a blog that I once followed (and still occasionally return to, hoping for an update), written by the first person I’d ever really encountered who had made practical the idea of living a life that meant something beyond simple accumulation. The first real, writing human being who asked the two questions “what do I believe” and “how do I live those beliefs”, and properly dedicated her life to bringing them together in an ever-imperfect, but ever-better dance.

There are times in my life when those questions have become more immediate and easier to make a life by. After a loss, or in the company of the right kinds of friends, for example. At those times, the questions seem so much clearer. Much easier to see clearly and act on courageously. But then there are times too, when the questions drift from me. When the things to be done in the everyday are momentarily more important, or life becomes snug enough to numb the intensity of such existential wondering.

The summer months here in Germany have marked such a drift. Fun, comfortable, and beautifully warm. But a drift nonetheless. It’s there, recorded in the datelines of the posts on this blog. Or rather, in the silences between them, and the half dozen semi-drafted ideas that sit waiting to properly become stories in their own right. I’ve been busy, mind you. On things that have a bit of that existential fire, and which try to approach the big questions and the limits of comfortable life and safe spaces. But also on things less radical. Less engaged in the politics of my life, and my deeper instincts.

Learning German in Göttingen, ahead of my second MA at the Willy Brandt school in September has undoubtedly been such a comfortable distraction. The degree itself being in English, and freed from any obligations to being tested at the end of the courses, class has mostly been an exercise in fun language play for those of us in this my cohort. Jokes about German compound words aside, language classes have frequently presented such entertaining distractions as mastering new ways to stack verbs in a sentence, or successfully navigate a train station. By way of illustration, imagine this scenario, if you will:

The enthusiastic student is asked a question by the teacher that they’d not specifically prepared for, and find themselves needing to produce a reasonably elegant (or at least functional) sentence under pressure. Student starts with some boilerplate sentence structure, only to hit a snag – in the case of German, this is frequently something to do with whether an object is male/female/neutral, or in trying to stick together one too many verbs. Their voice begins to waver.

Like a wounded gazelle surrounded by starved, functional-grade German hyaenas, they try to get back on their feet for a second run at the sentence. But all too often, they’ll be slaughtered where they lie by the jaws of a half-dozen prepared answers that have been silently practiced in the precious seconds that the victim has been hashing out the first sentence.

It’s brutal, but screamingly funny at times. Simultaneously both a competition with an Ayn Randian lack of empathy, and a David Attenborough-esque illustration of Darwinian language acquisition and reward-seeking behaviour. There’s blood on them colourful keycards, friend.

The Goethe Institute at night. All it needs are bats – though unsurprisingly it’s not as scary on the inside. In the daytime.

It’s also been incredible to see and feel the cognitive changes that take place over the duration of an extended and intensive language course. I’ve been in Göttingen since April, learning German pretty much every weekday for five hours a day in that time. On arrival, in the last days of winter, I spoke not a single word of German – barring perhaps some simple words learned from world war II comics and bad childhood movies. Few of which would probably have been anything but awkward. Most saliently, I couldn’t read any of the adverts on my first morning walks to class. I would pass perhaps ten or twenty posters and have literally no clue what they were saying.

Then, as the course progressed, the most curious thing began to happen. Each week that passed, some new piece of scenery began to acquire actual meaning. Signs on doorways. An ad for Tequila. Sexual health and evangelical church service notices. Lately even a poster for a lost and much-loved cat who doesn’t photograph too well.

Now, as the air has begun changing to what I assume will become autumn, and the end of class becomes visible on the horizon, I find myself able to properly read stuff, ask for stuff, and understand stuff with all the lexical dexterity of a nervous four year old. Which actually hides beneath levity what has been a terribly rewarding exercise in both affirming what it is possible to actually learn when you try, and in becoming comfortable with being imperfect. The sentence you really want is always out of reach. And there’s always something harder to read. In a moment of hubris, I bought a copy of Der Spiegel at the airport a week ago and promptly ran into a very perspective-correcting wall of language.

Now, like the too-perfect metaphor of summer, comes an ending, and a time to move on to the next cycle. I came here to learn specific things. About violence and stories and the capacities of each to remake the world. Because, to me, these are things that matter. And it would be forever unsatisfying to stray too far from the big battles, and the fires deep in hearts.

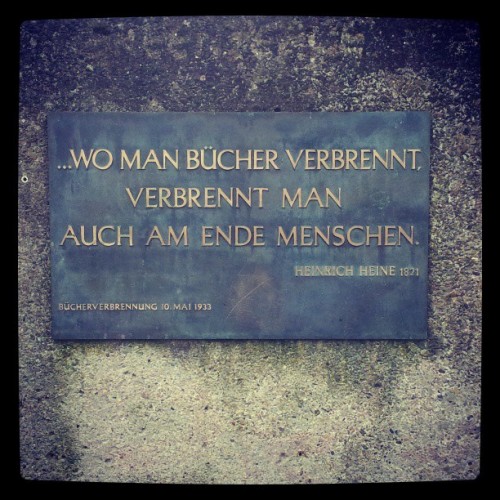

Ocasionally, on a less common route between home and class, there’s an iron plaque by the Göttingen theatre that – bolted inconspicuously to the wall – reads:

“Wo man Bücher verbrennt, verbrennt man auch am ende Menschen.”

Where man burns books, he burns people in the end. The parking lot just behind the plaque was a spot where the Hitler youth burned books. Before they and their ideas would later burn Europe.

It’s a reminder – amidst the tequila and the church services and the lost cat – that we can escape, intentionally or via an accidental drift, into a wonderland of word games and sentences about dogs and cats and trains. But, in the end, the two questions of belief and action lie everywhere around us.

It’s been great, great fun. But it’ll be good to feel a crisper wind again.